Art XXII

Research and study of the Ginga Kinubali pattern

RUBRIEK: Guppy Kweek Reworked (2022) on 15 February 2024

The reason for this was a question about the authenticity of purchased guppies. These were ginga's -in full ginga kinubali, which at the time were the breeding product of the Japanese grower Kenjiro Tanaka. Googling his name will unfortunately yield nothing: the best man has died in the meantime, and his site has been taken off the Net, so that at most you will get a Japanese baseball player with the same name as a result. The transience of existence is reflected today, to the extent to which one can or cannot be found on the Internet. Tanaka's name remains associated with the guppies he has bred, but there are no more publications about him; maybe in Japan, but not here. His ginga's are his heritage.

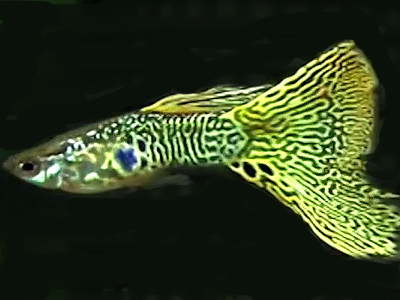

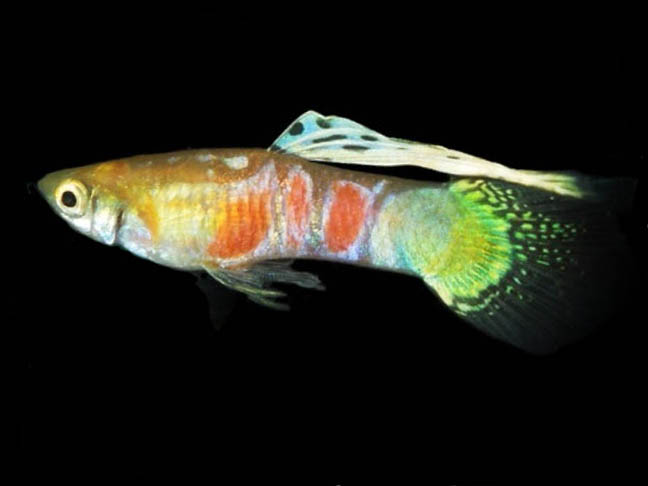

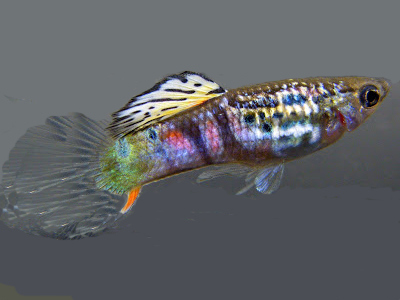

>Tanaka probably named his cultivated strain - literally translated "rice pastry" - after the beautifully decorated cupcakes that adorn the tables in Japan for dessert. I don't know if they were decorated with red stripes, but the photo above on the left is the best I've found that can approximate the image in my imagination. Because the ginga guppy, is a gem with vertical red stripes on the back body. These stripes are neatly parallel to each other, and of regular thickness, so that they appear to have been "painted" with a brush, as it were. They appear to have been carefully applied with calligraphy, as befits Eastern culture.

To understand why these red stripes look best on the blonde (=golden coatinglayer) guppy, it suffices to compare the two pictures on the right. See for yourself why a red rose looks so much better on a golden scale (= the sun); and a blue rose on a silver one (=the moon). To put it in Eastern terms: red and gold are yang (active, radiating, masculine,..) while blue and silver are yin (passive, absorbing, feminine,. ...). The red stripes therefore come out so muchbetter on the blonde ginga than on the grey ginga.

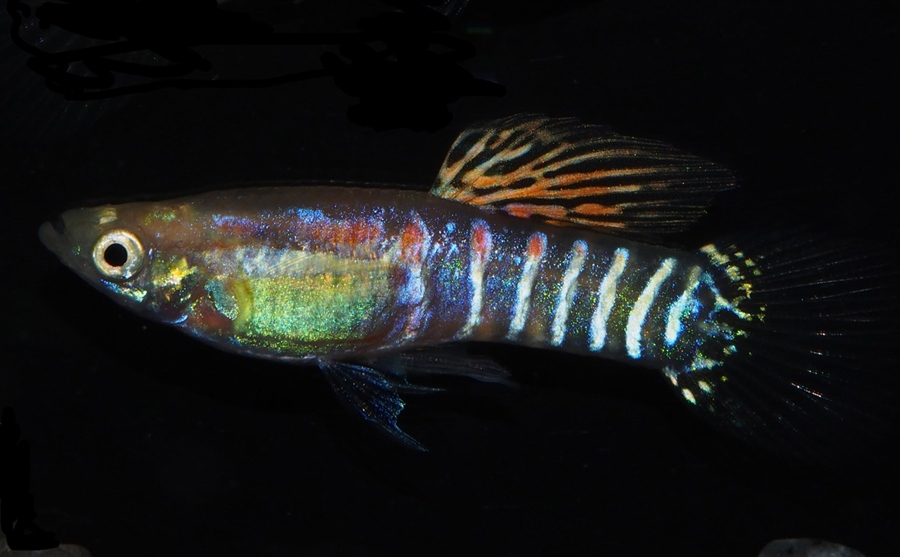

The red ginga -ginga rubra- caused a furore in the 80s, because it appea-led most to the imagination due to its flamboyant appearance. It's no open secret that Tanaka got his strain by crossing guppies with endlers. After all, the Zebrinus pattern in guppies is less thick and less even. Compare the stripes on the Snakeskin and the Wiener Emerald with those on the ginga, and you'll see what I mean. The stripe pattern in endlers is thicker and mo-re even, as can be seen in the Yellow Tiger, for example. The hybridization with endlers happened in the 80s, because the guppy breeding started to bleed out and everything had already been taken out of the guppy's genetic material. Crossing in endler patterns and colors brought a new lan to gup-py breeding.

The ginga rubra was a huge success, and from far and wide everyone wan-ted to get a few fish from Tanaka. That was then, but since then its novelty and sensation have faded considerably. And for a few obvious reasons. Primo, every self-respecting guppy breeder has already bred this strain. Second, and as is always the case when the trend has passed by: what now? After all, like any strain, this strain is also subject to the phenomena of regression: in offspring, the strain gradually starts to lose its calibrated properties. This is a completely natural process: the breeder carries through selection a narrowing of the hereditary material to a well-defined genotype and chosen phenotype, while NATURE tries to counteract this impoverishment by opening it up again. to break into the wild form with a wider heritable potential. Moreover, by switching from breeder to breeder, sometimes inferior or bland specimens were sold for the real stuff , so that the quality of the ginga deteriorated. And who would check or control that, if Tanaka himself was no longer there?

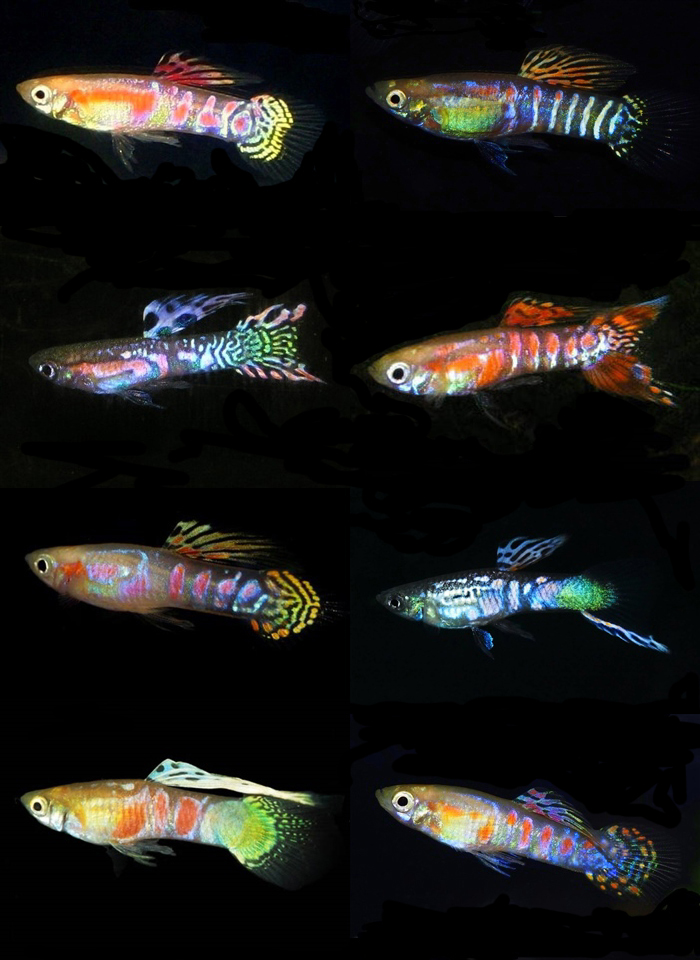

But to the regret of those who envy it, these criteria can still be establis-hed today by a careful investigation into the roots of the ginga strain, and understanding from there what could go wrong. Important are: the num-ber of stripes (varying from 4 to 6) as well as their length. When these stripes begin to decrease in number or when their length begins to shrink to spots as wide as they are long, the strain slowly but surely begins to lose its properties. Breeders have since tried to breed color variants, with varying degrees of success depending on the extent to which these vertical stripes on the hind body were retained. Of the examples you can see here, the Pink type is actually the only one that deserves the label "ginga" for this reason. And this applies to ALL the fish in the gallery on the left, all the way down to the bottom.

Secondly: the withdrawn figure that Kenjiro Tanaka was during his life-time has contributed to a certain myth-making, and the associated misunderstandings. On the one hand, they did not want to touch the merits of Tanaka having bred a new stock; but on the other hand, a lot of voices were raised that stated that the ginga was not a real strain, because the variability was too great. The latter is not correct, when one realizes that fish that are usually presented or sold as gingas - and again: that in-cludes all fish on the left - are strictly speaking NOT gingas. It illustrates that what is the ginga's greatest asset is also its problem: its richness of variation.

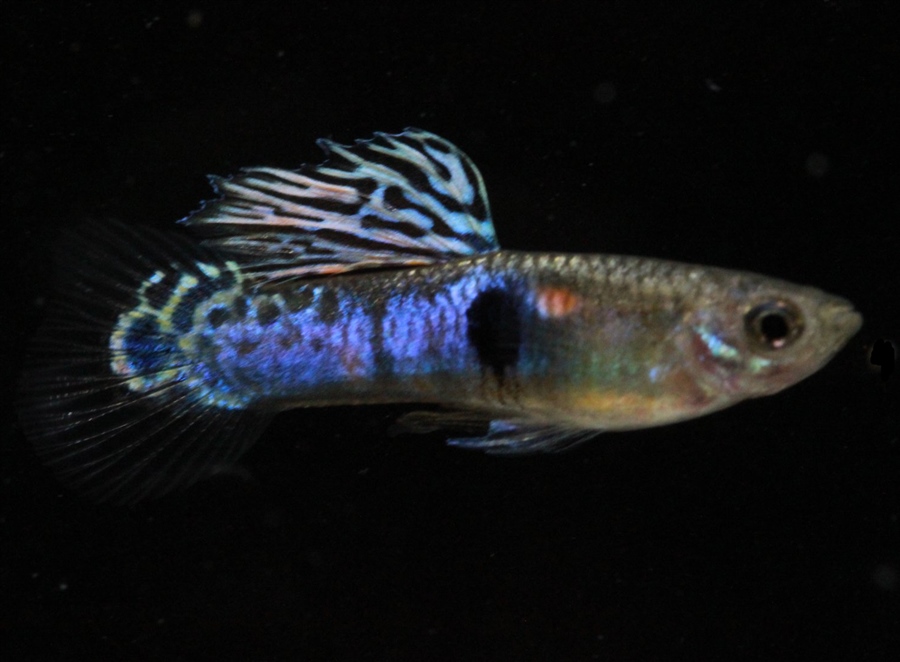

On the left is a gallery of guppies that CANNOT claim the Ginga label, with arguments as to why. The first is the product of an incrossing with a Bunt Vienna Emerald. He therefore shows the green caudal spot merging into a yellow lace tail, which, however, does not match the chocolate color of the body. The stri-pes are typical Vienna meanders, but therefore irregular in shape. Conclu-sion: This is a Vienna Emerald. The guppy below has the same crossbreeding background. In this speci-men the stripes are indeed nicely parallel, but they resemble a zebra (Ze-brinus). Strictly speaking, the orange dorsal fin is all that comes from the ginga, and the green sheen on the fore body is not in harmony with the rest of the color pattern. Conclusion: this is a Vienna Emerald. Number 3 is indeed blond and with some good will shows 3 ginga stripes. But half of the back body is occupied by the green caudal of Vienna + a little more blue. Conclusion: this is a Ginga/Vienna. Number 4 shows two stripes of a Vienna supplemented with a (weak) green caudal. The front body is that of a Snakeskin. Only a minuscule un-dersword points to possible Endler. Conclusion: this is a blond Ginga-Vienna. Number 5 shows even more Snakeskin influence. Four red spots and the dorsal fin hint at a possible Ginga background. Conclusion: this is a pale and poor Snakeskin. The guppies below those show a rear body that points toward Ginga influ-ence, but the front body is that of an old-fashioned wild shape. Conclusion: these are normal guppies with a Ginga/Vienna back body. The same goes for the copy purchased as "blue ginga". Blue is the front bo-dy, but this has to do with his story as a multi-color guppy. His Ginga story has broken down into 3 indistinct red dots, and both a dark/white division that has disintegrated and no longer makes a real coherent pattern. Its tail fin refers to a possible cross with a blue-green Double Sword strain. Con-clusion: This is a blue Double Sword/Ginga.

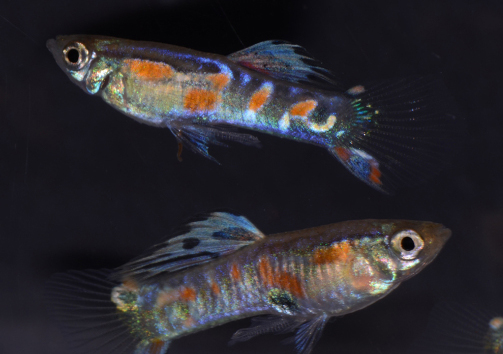

The larger photo below shows a purple-blue specimen that looks promi-sing, but in all likelihood has some serious issues for potential improve-ment. The blue Peacock eye on the caudal fin and dorsal fin evoke asso-ciations with early Snakeskins; which may also explain the black spot in the middle of the body. But why doesn't the front body have any color at all? If Asian Blau would have been used, this is the best one can achieve.

On the next set of photos on the left, the Ginga influence is still clearly noticeable, but the regression described above has struck. This results in Ginga patterns that are literally "beaten apart" into loose drawings and figures, (photo 1); to a reduction in the intensity of the pattern or colors (photo 2): to the insertion of other patterns, making the guppy literally a sort of composite or patchwork blanket. Sometimes these different pat-terns merge, but the result remains a heterogeneous "mixture" that looks unnatural (photo 3). Sometimes those different patterns are comparted according to the different segments of the body. In photo 4 one can see such an example: the breast area is simply multicolored; the mid-body exhibits Ginga properties; and the rear body is that of a Vienna. Photo 5 shows how the original ginga pattern in a blond strain (fish below) can degrade to what one calls Pidgeon Blood.

If one does not want to let the Ginga properties disappear further, then one must take the bottom male for further breeding. It is no public secret that in order to keep a stock stable, one must constantly select to ensure that his fish remain of quality. Only about 20% of a litter is usable for the next generation. The shadow side of selecting is elimination, as I have high-lighted in my article Guppy Breeding: Selecting and Eliminating. According to some "puritans" the Ginga is not a real" strain because it has too much variability Technocrats and people who want to be more Catho-lic than the Pope can be found everywhere, but this is bullshit. Breeding identical clones may be a guppy designer's wet dream and a mass guppy breeder's wet dream, but the reality is that it is NOT in the best interest of the fish itself to arrive at a fixed genome.I have explained this problem in Guppy: rigid strains or rich variations.

You may have while you were surfing the Net about guppies find the photo below. You can recognize a lot of photos that were used also in this article here. Then you immediately know that this is a piece of work by me : with monks' patience I "cut" each fish from its original background, and then placed them next to each other on a black background. After all, I am not the only one who has noticed that the colorful guppies show their best color when placed or photographed on a dark background . It doesn't bother me that others have taken over this plate without request, because this is actually the proof that they liked it. I even found my piece of work on a sales site, phew haha! With this parade I wanted to display the richness of color and variety of the Ginga. It is an ode to the fish, and in a way also to Tanaka, although I have never had contact with the man.

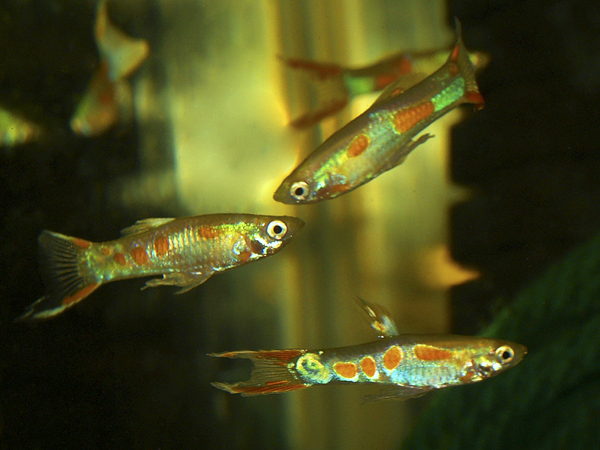

However, the reason for the misunderstandings lies in a completely different direction. The reason why you won't find the Ginga Kinubali treated as a separate guppy strain among all the other fancy guppies is the same reason why digital photography produces such impossibly sharp images. The reason that immediately became clear to me when I decided to order gingas as a birthday gift to myself. That's the very first time I've done this, because for all the other guppy strains I've bred, I've always started with ordinary ones I bought at the aquarium stores. When I was able to take a look at the fish carefully packed in a plastic bag, it immediately became clear to me that gingas... ARE NOT GUPPIES. When males grow to only 2cm in size and females grow to a maximum of 4cm, they are ENDLERS, and not guppies. Although guppies and endlers are very closely related to each other, they differ enough to be cataloged as different subspecies: the guppy as Poecilia reticulata, and the endler as Poecilia wingei.

The well-kept secret that is the basis of all misunderstandings surrounding the gingas is ...... that the gin-ga is an endler, and not a guppy. Calling both species colloquially as "guppies" is tantamount to confusing plaice with plaice, koi with goldfish, or leopards with jaguars, for example. This immediately makes a few things clear. First, that the distribution of band stripes on the hind body is a typical endler pattern found in both the ginga and the tiger endler. Secondly, that the lace tail and the green caudal come from the guppy because both belong to the primordial strains of the guppy as I said in Genetic Genealogy Table of Strains, which is not only the basis of the Lace-tail in Snakeskins, but also partly occurs in the Vienna Emerald. The problem with all those perfect and razor-sharp and therefore highly enlarged photos is that one can no longer estimate the true size of a fish. In a container with plants, the eye has these reference points. See for yourself the difference between gingas and guppies in the film below.

However beautiful the gingas may be, I experience them first and foremost as little fish, which I have to look at with a magnifying glass, as it were, to see their beauty. For me personally, Gingas are too small, especially because I am used to selecting my guppies not only by color but also by size. Of course I can try to hybridize them with guppies, but then I will most likely end up with fish like the ones in the gallery on the left. According to my own forecast, crossing guppy females with ginga males will produce more Snakeskin-like young with lace tails; and the crossing of female ender with guppy male pale multi-fish as in photo 5, counted left from bottom. So I really don't know whether it makes sense to disintegrate Tanaka's work in the opposite sense.